Home | ss CITY OF CAIRO

This is the story of the sinking of the ss CITY OF CAIRO. I decided to write these pages after the death of my father, Calum MacLean (1922 – 1996), who served aboard this ship as a young quartermaster. I had accumulated a lot of research material and decided there was little point in keeping it hidden in a drawer.

This Site is the result of many years of research using primary records and first-hand accounts. I also corresponded with the author of 'Goodnight Sorry for Sinking You', Ralph Barker (1917 – 2011), who wrote the definitive account and first brought this story into the public domain in 1984. He was enthusiastic and more than helpful to me and I would thoroughly recommend his book to you.

It was also my pleasure to talk to some of the survivors of the sinking and their families, and I am grateful for all the help and encouragement given to me. It should be read in conjunction with the many other accounts, documents, letters, and photographs that are also available on this Site.

From One War to Another

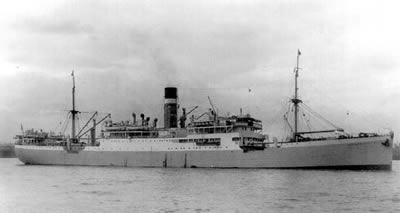

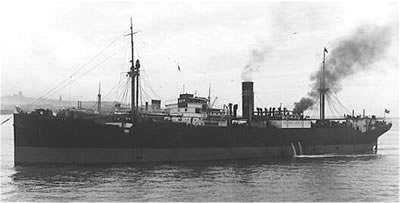

ss CITY OF CAIRO - In wartime livery

Copyright © and courtesy John Clarkson

The Ellerman Line’s ss CITY OF CAIRO began her life in one war and ended it in another as one of the group's most tragic losses. She was built by Earle's Shipbuilding and Engineering Co. Ltd in Hull and registered at Liverpool in 1915. She sailed under the management and colours of the Hall Line under requisition. The ship was a single-screw steamship with two decks and two masts, schooner rigged, and had a burden of 8,034 tons. She was 450 feet long, had a beam of 55 feet 8 inches, and her two 386 hp engines gave her a cruising speed of 12.5 knots. The maiden voyage from Liverpool sailed on January 23, 1915, and terminated at Birkenhead on May 23, 1915. The ship’s first master was Captain Frederick William Parker from Bristol.

Towards the end of World War I, she was employed as a troopship, transporting U.S., Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand troops to and from the UK. Sadly, just before the Armistice, many soldiers died aboard or shortly after arrival in England from the Spanish Flu pandemic, which was raging at that time.

World War II: The Final Voyage

On Thursday, October 1, 1942, the steamship ss CITY OF CAIRO, with its hull painted in a wartime grey livery, was waiting under the hot Bombay sun for her passengers and cargo to finish boarding. The 450-ft long vessel had seen better days but was in reasonable shape for her 27 years and had completed a Special Survey at Durban only two months earlier.

Despite her outward appearance, the ship offered comfortable cabins with electric fans to combat hot and humid weather. Passengers could also enjoy amenities such as a canvas pool, a well-stocked bar, and a small library. The ship's reputation for providing an enjoyable and leisurely voyage was further enhanced by her professional and friendly crew. Elegant public rooms furnished in the Edwardian style, including a dining saloon, music room lounge, and smoking room, added to the overall appeal.

As departure time approached and passengers settled into their cabins, a convoy of trucks accompanied by an army patrol and heavy police presence suddenly arrived alongside the ship. The trucks swiftly unloaded a significant number of rectangular black boxes, which were deposited into No.4 Hold. Observing the cargo being loaded from the after-well deck, the ship's surgeon, Douglas Quantrill, wondered about the contents of these boxes – something highly valuable, apparently, to warrant an armed security guard. A secret telegram from Bombay to the War Office dated 5 October 1942 confirmed that the ship was loaded with 2,182 boxes of silver bullion weighing 122 tons. It was certainly a departure from her usual cargo of pig iron, timber, wool, cotton, and manganese ore, which had already been loaded into the other holds.

The ship sailed independently on the morning of October 2, 1942, and proceeded on her voyage from Bombay, Durban, and Cape Town for the United Kingdom via Pernambuco (now called Recife) in Brazil. The total complement was 302, of whom 101 were fare-paying passengers, 29 were women and there were 18 children. The crew also included 10 D.E.M.S. (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships) gunners from the Army and Royal Navy and two spare Lascar crews recruited in India for ships under construction in the United Kingdom. The voyages to Durban and Cape Town were uneventful, but the average speed of the Durban leg was below 10 knots, which was a concern for the crew. If they could not maintain the regulation 10 knots necessary for carrying passengers, they would have to be disembarked at Cape Town. However, the captain was confident that the ship, once properly bunkered and the fires cleaned and raked, could sail at their advertised speed without making smoke. The ship duly reached Cape Town within three and a half days, and the license to carry passengers unescorted was safe.

With no fast escort vessels available, N.C.S.O. (Naval Control Shipping Officer) Cape Town routed the CITY OF CAIRO for a lone crossing of the South Atlantic to Pernambuco, avoiding the U-boat-infested Freetown route to the north. The master was confident of reaching Pernambuco in 15 days.

Torpedoed at Sea - A Sudden and Devastating Attack

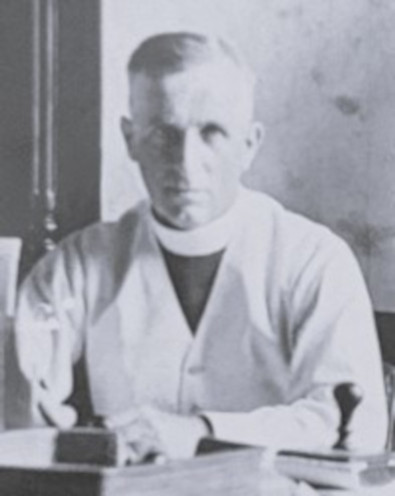

Captain W.A. Rogerson

Copyright © Ralph Barker

After a three-day stopover, the ship sailed independently from Cape Town on Sunday morning, November 1, 1942. The master, Captain William Rogerson, a 46-year-old Liverpudlian, was ordered to steer a mean northerly course parallel with the African coast for 800 miles, zig-zagging during the day and keeping about 45 miles out. At latitude 23.30 South, he was to turn due West, straight out into the South Atlantic. Not until he was in the mid-Atlantic would he turn northwest for Pernambuco.

On Friday, November 6, 1942, at 20:26, the ship, in position 23°30'S 05°30'W, was struck by a torpedo abreast of the after-mast. The torpedo was fired by U-68, commanded by Karl-Friedrich Merten.

Abandoning Ship - Ordering the Evacuation

Passengers and crew made their way to their boat stations, momentarily losing their bearings as the lights dipped, flickered, and went out. The ship, still underway, had stabilized, but it was slowly settling by the stern. Captain Rogerson issued the following order: "Prepare to abandon ship! Lower the boats!"

At that time, Second Radio Officer Tom Humphries was on watch in the wireless office. He sent out a distress call, which was quickly acknowledged by the U-boat, giving the callsign of the Walvis Bay station in South Africa.

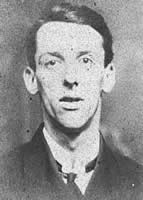

Chief R.O. Harry Peever

Lost at sea 6.11.1942

Chief Radio Officer Harry Peever took over in the wireless office and was still aboard when the second torpedo hit. He was one of the six people killed in the initial attack.

The boats were lowered and attempted to move away from the ship. After about twenty minutes, Merten loosed a second torpedo, and the CITY OF CAIRO sank by the stern. The submarine surfaced and, speaking to the occupants of No.6 boat, asked the ship's name, cargo, and whether it was carrying prisoners of war. He then gave a course for the nearest land, approximately 2,000 miles from Brazil, 1,000 miles from Africa, and 500 miles from St Helena. Kapitan Merten then uttered the now-famous phrase: "Goodnight, and sorry for sinking you," and departed the scene.

The Right Honourable Alfred Barnes, Minister of War Transport - July 1945.

Survival in Open Boats - Navigating Towards Safety

Captain Rogerson, although very unwell after swallowing a lot of seawater at the sinking, gathered the boats together to assess the situation. It turned out that six people had perished during the sinking, two crew members and four passengers. Rogerson decided that their only hope was to try to make it to St Helena, which was 480 miles away. The tiny island in the middle of the South Atlantic would be difficult to navigate to in open boats, and there was a distinct possibility of overshooting the island.

There were six open boats containing 296 souls, and Rogerson in No.5 boat had to somehow guide them to safety. Each boat had an officer in charge, although boats 6 and 8 had Merchant Navy officers in charge who were not members of the ship’s crew. All of them would give good accounts of themselves during the ordeal. All of the boats had a compass, but only Second Officer Boundy in No.7 boat had a sextant, which he had retrieved from his cabin. This, along with Rogerson's Rolex Oyster watch, meant that they all had to stick together to give them the best chance to navigate to St Helena.

Francis A. Marr

Lost at sea 6.11.1942

Lauchlan McLean

Lost at sea 6.11.1942

Photos Courtesy of Felix Jackson and Lauchlan MacLean.

Separation and Desperation - A Race Against Time

Courtesy of Paul Reed

Lest We Forget

Tower Hill Memorial

The boats were at sea for about a week when the first separation occurred. Chief Officer Britt in No.1 boat requested to go on ahead, as his boat was short of rations and taking in water, but he also had the fastest boat. Rogerson, who had wanted to avoid a boat race, initially refused this request. He believed that the key to their survival was Boundy's sextant, so they had to stay together. However, on Wednesday, November 11, Rogerson reluctantly allowed Britt to go on ahead.

By this time, all occupants of the six boats were suffering and there were deaths in all of the boats, water was strictly rationed, and the food was too dry to eat. Structural damage to the boats also occurred. No.7 boat had no rudder as it was blown away by the explosion of the torpedo, so a steering oar was rigged until a jury rudder could be fitted. No.8 boat had a cracked mast that was temporarily repaired by the two quartermasters Campbell and McKelvie, using an oar as a splint. The remaining boats were also struggling to stay in touch. On Friday, November 13, they lost touch with No.6 boat (George Nutter), and Third Officer Whyte in No.4 boat was also struggling to stay in touch. Rogerson now had an agonizing decision to make: to stay and wait for Nutter in No.6 boat or to push on. He felt he could no longer sacrifice the progress of the majority to round up the stragglers. The boat race was on. On Friday night, November 13, boats 4 and 8 were now together, having lost touch with the rest. With those two boats, progress was very slow, and the fault lay with No.8 boat. Tommy Green, in charge of No.8 boat, advised Britt in No.4 boat to push on without him. It was November 15, the second Sunday since the sinking, and Whyte, like Britt before him, set out on his own.

A Glimpse of Hope - Rescue and Recovery Aboard the ss CLAN ALPINE

ss CLAN ALPINE

Courtesy of Raymond Forward

Early in the morning of Thursday, November 19, No.6 boat, which was some way behind Rogerson and Boundy in No.5 and 7 boats respectively, sighted a ship on the horizon. This was the ss CLAN ALPINE en-route to St Helena. Captain Charles W. Banbury brought his ship alongside to recover the survivors. George Nutter explained the situation to the master, mentioning that there were other boats ahead of him. He had been the first to lose touch and was unaware that there were also two boats behind as well: No.1 boat and No.4 boat.

On the CLAN ALPINE, the second officer reported that two more boats were in sight. By 08:20, the ship was alongside No.7 boat, and after the occupants were safely aboard, it was the turn of No.5 boat. Sadly, even during the rescue, there were deaths of survivors aboard the CLAN ALPINE and also at St Helena Hospital after the ship had arrived.

Remaining Boats and the Journey's Grim Toll

ss BENDORAN

Tommy Green

Joe McMillan Collection

Meanwhile, boats 1, 4, and 8 were still at sea. No.8 boat, under the charge of Tommy Green, who was a Chief Officer in the British India Steamship Navigation Company and a master mariner, didn't have long to wait. That same evening, November 19, they were picked up by the ss BENDORAN, an 8,500-ton cargo carrier from the Ben Line under the command of Captain William C. Wilson. Boats 5, 6, 7, and 8 had been at sea for 13 days before rescue.

At the same time as the rescue of some of the other boats, things were getting desperate in No.1 boat. Chief Officer Sidney Britt collapsed that night, and by the fifteenth morning, he was among the dead. By the same evening, Capt. Thomas McCall, also a master mariner who shared the navigation with Britt, was also dead, leaving no one with any navigational qualifications left. Reduced in numbers by half, the survivors needed a new leader, and Quartermaster Angus MacDonald took over. MacDonald was experienced in small boats and was assisted by Third Steward Jack Edmead and passenger Diana Jarman. As the days passed, more of the occupants died.

The German Blockade Runner RHAKOTIS and a Deadly Encounter

On December 12, 1942, after 36 days at sea, 51 of their number had died, and only three were left alive. They were picked up by the German blockade runner RHAKOTIS. Kapitan zur See Jacobs told them that they had come a long way past St Helena, five hundred miles to the northwest. The survivors were Quartermaster Angus MacDonald, Third Steward Jack Edmead, and passenger Diana Jarman. Their elation at survival was short-lived with the death onboard the RHAKOTIS of Diana Jarman, who had bravely shared their ordeal.

There was more to come, as the RHAKOTIS was due to rendezvous with U-boats around December 27, 1942. British Intelligence was also trying to find her, and on New Year's Day 1943, the RHAKOTIS was attacked by the British Cruiser HMS SCYLLA. MacDonald and Edmead managed to get to different lifeboats before the RHAKOTIS sank. HMS SCYLLA, fearing the U-boats, never stopped to pick up survivors.

MacDonald and Edmead's Fate and Margaret Gordon's Courage

The next day, January 2, MacDonald was picked up by U-410 and survived a depth charging attack by British bombers. He was eventually landed and spent the rest of the war in Marlag and Milag Nord prisoner-of-war camp at Westertimke. Jack Edmead's lifeboat, under the charge of the RHAKOTIS' chief officer, landed in Corunna, Spain, on January 3, 1943.

Angus MacDonald and Jack Edmead were both awarded the BEM(Civ). Sidney Britt was commended for his brave conduct. When the Guards Armoured Division overran Milag Nord Prisoner of War camp in May 1945, Frank Ironside, brother of Bob Ironside, was one of the men who cut through the wire. Hearing that one of the survivors was from the CITY OF CAIRO, he sought out the man. Angus MacDonald still had his quartermaster friend's Signet ring in safekeeping, and he gave it to Ironside, who recognized it at once and sent it home. Angus MacDonald wrote his own account of the sinking, "Ordeal," referred to by Alan Villiers as “the classic open-boat story of World Wars 1 and 2”.

In No.4 boat, with 17 people onboard (10 Asians, 7 Europeans), Third Officer Whyte realized that by November 20, he should have sighted the island of St Helena. By Monday, November 23, all of Whyte's Asian crew had died, and he decided to abandon the search for St Helena and turned west-northwest for South America.

Now the Europeans started to die, and the only woman on board, Margaret Gordon, an Australian, nursed them as best she could. Whyte also relied on her more and taught her how to steer the boat and use a compass.

On December 27, 1942, after 52 days at sea in an open boat, the Brazilian Carioca-class minelayer CARAVELAS rescued Third Officer Whyte and Margaret Gordon, the only two left alive. Since setting off on their own on November 13, they had covered over 2,000 miles.

Unfortunately, like No.1 boat, there was a sad ending to this account of enormous endurance and survival. Third Officer Whyte was hospitalized in the USA for a short time and then, after recuperating, he boarded the Ellerman vessel CITY OF PRETORIA as a distressed British seaman on his journey home. The ship, carrying munitions, disappeared without trace. Later, from enemy records, it was discovered that the ship was torpedoed by U-172 (Carl Emmerman), and there were no survivors.

James Allistair Whyte was awarded the MBE(Civ) backdated to the day before he was killed. Margaret Gordon went to New York in 1943 and became a member of the WRNS. A year later, in Washington D.C., she was presented with the BEM(Civ) for her courage and service in the lifeboat.

Conclusion - An Unforgettable Saga of Endurance and Loss

Of the total complement of 302, just over one third did not survive. Lost either during the sinking, the journey in open boats, died after rescue or in the case of Third Officer Whyte tragically killed while being transported back to the UK after recuperation. A total of 108 passengers and crew who were aboard the ship on leaving Cape Town did not make it back home. Lest we forget.

Most of those who did come home to their families, their lives were inevitably never the same again.

The full list of awards to this ship were as follows: Captain William A. Rogerson was awarded the O.B.E.(Civ) and Les Boundy, James Alister Whyte, George Nutter and Tommy Green were awarded the M.B.E.(Civ). Patrick MacNeil and Margaret Gordon were awarded the B.E.M.(Civ).

Commendations for brave conduct were awarded to: Chief Officer Sidney Britt (posthumous). Chief Engineer Robert Faulds. Passenger Gladys Usher. Surgeon Dr. Douglas W. Quantrill.

Lifeboat No. 5, 6, 7 and 8 spent 13 days at sea.

Lifeboat No. 1 spent 36 days at sea.

Lifeboat No. 4 spent 52 days at sea.

There are some amazing individual stories on this site concerning some of those aboard. I would urge you to read them. Quartermaster Angus MacDonald, who survived 36 days adrift in an open boat and was rescued by a German blockade runner which in turn was also sunk by the British Navy and he found himself abandoning another ship and into another lifeboat and being rescued again by a German U-boat which was depth-charged by the RAF but survived, was landed and he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war.

The tragic story of Diana Jarman the war-widow who also survived 36 days only to die aboard the blockade runner. Her parents frantically trying to obtain information about her only heard of her death in the media.

The poignant story of James Knocker Whyte who survived 52 days in an open boat picked up by the Brazilian Navy and after a period of recuperation was being repatriated back home to the UK on another Ellerman steamship, CITY OF PRETORIA when it was torpedoed and lost with all hands. Lest we ever forget.

Every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material, and

I hope no breach of copyright has occurred. Please contact me at the address

below if any infringement has taken place. Pardon is sought and an apology

given if the contrary is the case. Any amendments or corrections will be

issued at the next update.

By the same token this site contains copyright material and, you are respectfully

reminded, that any reproduction is both illegal and immoral without the

express permission of the copyright holder. All copyright holders, where

known, have been recognised in the Acknowledgements section of the site.